From the earliest encounters between settlers and Indigenous nations to modern immigration enforcement, the United States has relied on forced removal, deportation, and exclusion as tools of control. Indigenous nations, enslaved Africans, free Black communities, religious minorities, Asian immigrants, Mexican and Mexican American families, Japanese Americans, and more recent immigrant groups have all faced it. The reasons shift — territorial expansion, national security, economic fears, or racial prejudice — but the underlying logic has remained hauntingly consistent.

European colonization in the 1600s brought displacement almost immediately. King Philip’s War (1675–78) in New England left survivors killed, enslaved, or sold overseas, setting a precedent for mass removals. Spanish missions in California and the Southwest confined Indigenous peoples into systems of forced labor and cultural erasure, creating blueprints for later policies.

After independence, the new United States followed a similar path. Treaties like the Treaty of Greenville (1795) stripped Indigenous nations of millions of acres in the Ohio Valley. These agreements, coerced after military defeats, normalized the idea that land could be taken by force, then legalized through paper.

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

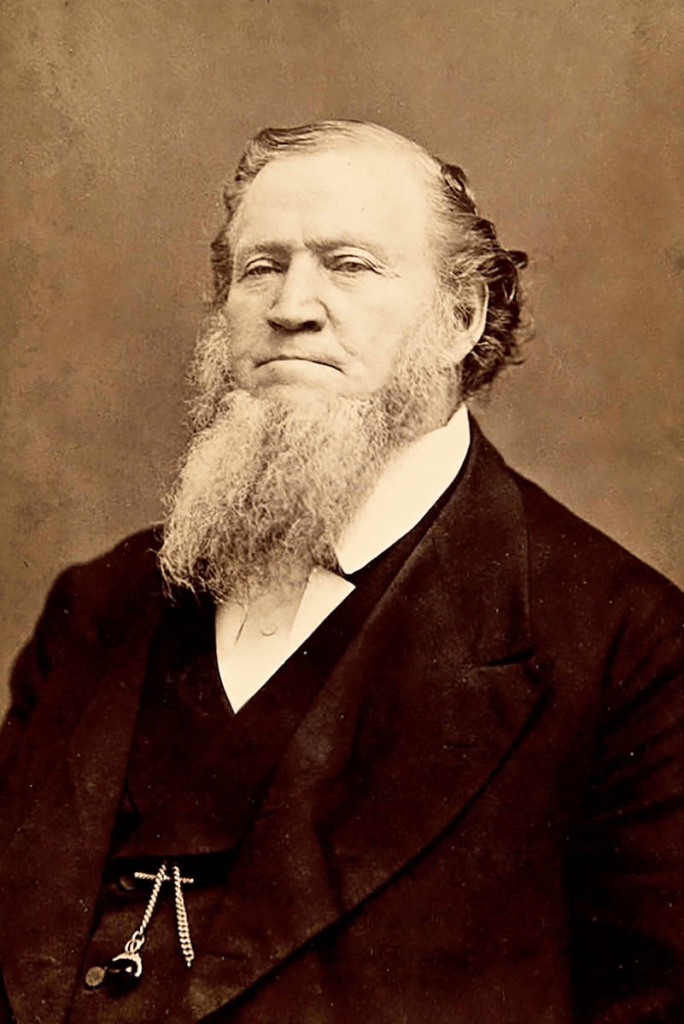

Religious minorities were not immune. In 1838, Missouri’s governor issued an “Extermination Order” mandating the removal of Mormons, forcing thousands to flee. Yet in exile, the group took on another role. Migrating west to the Great Basin in the 1840s, Mormons became colonizers themselves. Their settlement of Utah sparked violent clashes with Indigenous nations, including the Walker War (1853–54). What began as survival turned into expansion, showing how groups displaced in one era could perpetuate cycles of removal in another.

Removal and Expansion

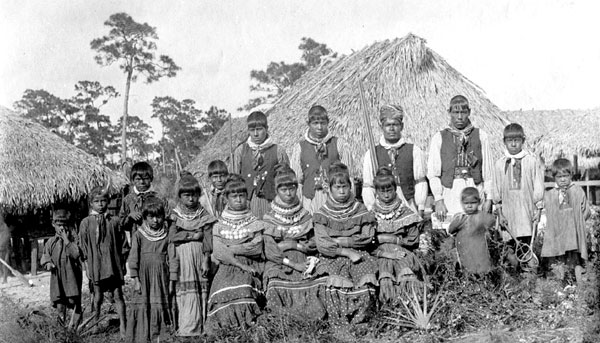

These precedents culminated in the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The policy gave the federal government authority to uproot Native nations wholesale. The Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, Chickasaw, and Seminole peoples were forced from their homelands in the Southeast and marched to “Indian Territory.” Tens of thousands died on the Trail of Tears, while millions of acres were opened for white settlement.

The Seminoles of Florida resisted most fiercely, aided by free Black communities who had fled enslavement. This alliance made both groups targets. U.S. forces sought not only to seize Indigenous land but also to dismantle free Black settlements, treating them as threats to the institution of slavery. Here, the logic of removal converged: Indigenous sovereignty and Black freedom were seen as incompatible with the expansion of the United States.

The transatlantic slave trade brought millions of Africans to the Americas in chains. Their forced labor became the backbone of the U.S. economy, and racial hierarchy was cemented into law and culture. Enslavement was itself a system of removal — tearing people from homelands, families, and identities, while violently excluding them from belonging in the nation they built.

Even after slavery’s abolition, exclusion shifted forms. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 became the first federal law to explicitly bar an entire nationality. Framed as protection of American workers, it was fueled by racial stereotypes and fears of economic competition. The law introduced deportation as a formal mechanism and created a template for racialized immigration policy.

Depression-Era Deportations: Mexican Repatriation

During the Great Depression, Mexican and Mexican American families became scapegoats for job scarcity. Between 1 and 2 million people were deported or pressured into “voluntary” repatriation — despite as many as 60% being U.S. citizens. The pattern repeated in Operation Wetback (1954), when raids swept through fields, factories, and neighborhoods, deporting hundreds of thousands. Both episodes reveal how economic crises turned vulnerable communities into targets.

World War II brought another wave of removal. After Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, ~120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, most U.S. citizens, were forcibly relocated under Executive Order 9066. Families lost businesses, farms, and homes while being held in inland camps. No evidence of disloyalty was ever proven. Historians now widely recognize this as one of the most glaring examples of racialized wartime hysteria sanctioned by federal power.

By the late 20th century, immigration enforcement was woven into U.S. law. The 1996 IIRIRA expanded deportable offenses and slashed judicial review. After 9/11, the creation of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) redefined immigration as a matter of national security. Today, mass detention and deportation remain central to U.S. policy. Reports show that the majority of detainees have no criminal history, yet they are confined under a logic of deterrence and control that echoes past eras.

Why the Pattern Endures

Social scientists identify recurring logics behind these cycles:

- Settler-colonial logic (Patrick Wolfe): Indigenous removal is not an anomaly but a structural feature of settler states.

- Scapegoating theory (René Girard): In times of crisis, minorities become symbols of blame — Mexicans during the Depression, Japanese during WWII.

- Social Identity Theory (Tajfel & Turner): In-groups enforce dominance by excluding out-groups.

- Dehumanization (Nick Haslam): Stripping groups of “humanness” enables violence and coercion.

- Moral panic (Stanley Cohen): Leaders and media amplify threats, justifying extreme measures — from “yellow peril” to “criminal alien.”

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

Across centuries, forced removal has shifted forms: wars of conquest, coerced treaties, religious expulsions, racialized immigration bans, mass deportations, wartime incarcerations, and modern detention. Different groups have been targeted at different moments, but the logic remains constant. When those in power perceive a threat — to territory, economy, religion, or security — removal becomes the solution. Recognizing these continuities reframes today’s debates on immigration and belonging. They are not isolated disputes but part of a long cycle that can only be broken by learning from history rather than repeating it.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.