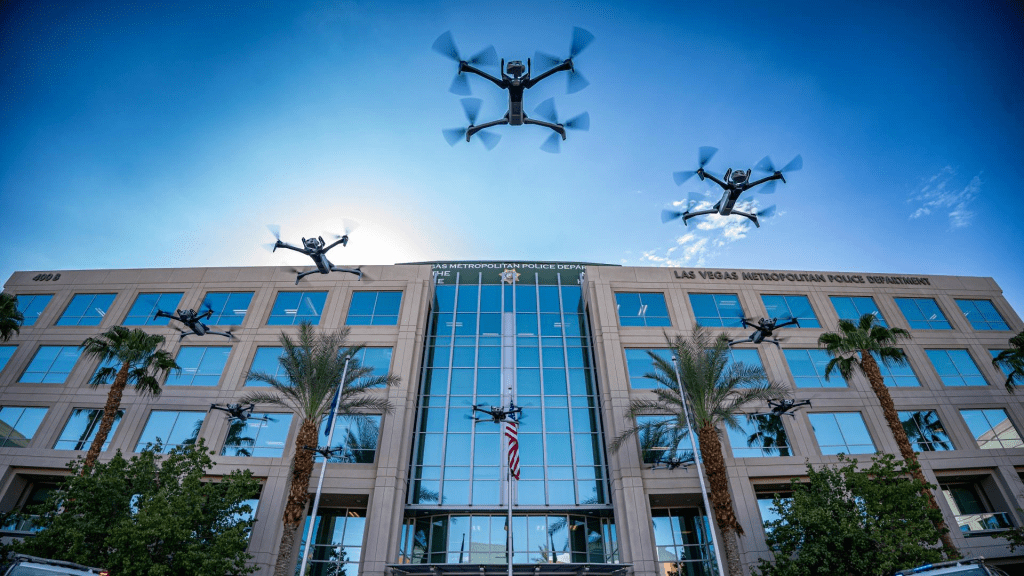

When the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department (LVMPD) announced Project Blue Sky, the program was pitched as a leap in public safety. With 75 drones launched from 13 “Skyports” across the valley, operated by a centralized team, police said response times would shrink and situational awareness would grow.

But beneath the promise lies a deeper story — one where surveillance technology, venture capital, and housing power converge in ways that could reshape who feels safe, who feels watched, and who can afford to live in Las Vegas.

Public Safety or Expanding Surveillance?

LVMPD frames the drone program as a modern tool for first responders. Drones can search for missing persons, map traffic collisions, and give firefighters eyes on dangerous blazes. Department policy stresses privacy — no flights over private backyards without a warrant, flight logs and audits, and automatic deletion of non-investigative footage after one year.

Yet privacy advocates warn that the scope of surveillance rarely shrinks once infrastructure is in place. The ACLU of Nevada has raised Fourth Amendment concerns, while scholars like Dr. Joy Buolamwini have pointed to AI-driven systems’ tendency to reproduce bias. Surveillance tools often claim neutrality, but their deployment most often lands hardest on Black, Indigenous, immigrant, and other already vulnerable communities.

The Investors Behind the Program

While the technology raises concerns, so too does the funding model. Project Blue Sky isn’t just taxpayer-supported — it’s also financed through private donations and community contributions. That opens the door to influence from investors whose interests extend far beyond public safety.

Take Skydio, the California-based drone company whose autonomous X10 models are central to LVMPD’s fleet. Skydio is backed heavily by Andreessen Horowitz (a16z), one of Silicon Valley’s most powerful venture firms. A16z has poured money into proptech — property-technology startups like Flow and EliseAI — while its co-founders Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz have made high-profile luxury real estate purchases in Las Vegas. Ben Horowitz even personally donated funds to help the LVMPD acquire Skydio drones.

This creates a rare overlap: the same investor network helping to expand Las Vegas’ surveillance infrastructure is also tied to the city’s housing market. In a region where housing affordability is already strained, critics worry that tech capital is being channeled into both the policing of space and the reshaping of who gets to live in it.

By contrast, other drone suppliers have fewer local entanglements. Brinc Drones, another LVMPD partner, raised funds from Index Ventures and Motorola Solutions, whose footprint in the valley extends further through its license-plate-reader (LPR) business. Skyfront relies on robotics-focused venture funds, and Teledyne FLIR, a large defense-contractor subsidiary, is powered by institutional giants like Vanguard and BlackRock — whose ties to real estate are broad but indirect. Still, the most visible and immediate connections remain those of a16z, where policing and property investments converge most clearly.

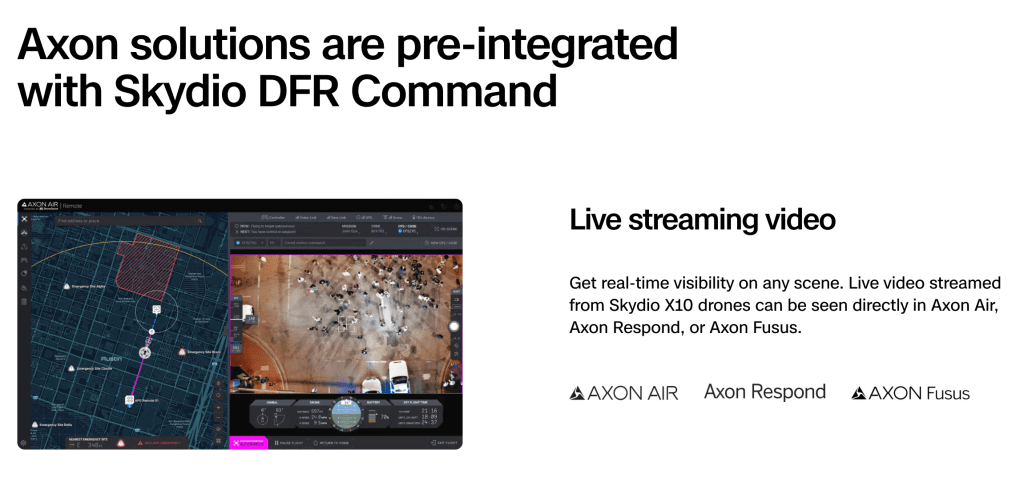

The Axon–Skydio Nexus

A critical axis of influence lies in how the drone infrastructure is financed and supplied. Skydio’s drones are central to LVMPD’s fleet, and through its partnership with Axon — the company behind body cameras, tasers, and evidence-management platforms — these tools are being integrated into a broader policing ecosystem. The result is a powerful data pipeline: drones, cameras, and sensors all feeding into centralized evidence repositories controlled by a small number of private firms.

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

But what makes this partnership more troubling is the overlap in their investor base. Andreessen Horowitz (a16z) is not only a major backer of Skydio but also one of the most aggressive venture firms in the property-technology sector, investing in startups like Flow and EliseAI that seek to reshape housing markets. Meanwhile, Axon’s largest institutional shareholders include Vanguard and BlackRock — asset managers that hold vast stakes in real estate investment trusts (REITs) and rental housing nationwide. Together, these investors occupy a dual role: underwriting the expansion of surveillance technologies while simultaneously driving trends in housing markets.

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

That convergence creates a conflict of interest. If the same networks profiting from rising property values are also supplying the tools that police public space, then surveillance and housing affordability are no longer separate issues — they are two sides of the same strategy. In Las Vegas, a city already grappling with affordability crises, the Axon–Skydio nexus raises the specter of a future where the investors behind the police’s eyes in the sky are the same ones shaping who can afford to live beneath them.

Motorola The Added Eyes’

License-plate readers (LPRs) are a street-level counterpart to airborne observation, and Motorola Solutions has been a major vendor in that market. Portable LPR units can be deployed rapidly at traffic “hotspots,” feed license-plate data into databases, and support investigations and automatic alerts. In metropolitan areas, LPRs create continuous, machine-readable records of vehicle movements that — when linked with other datasets — produce detailed mobility maps of residents’ daily lives.

Security researchers have previously demonstrated that vulnerabilities in LPR and connected camera systems can expose live feeds or stored plate data, underscoring how fragile the safeguards around this infrastructure can be. In Las Vegas, the combination of drones above and LPRs on the street risks producing a layered surveillance architecture: aerial observation, vehicle tracking, and event footage aggregated and searchable in ways that go far beyond the departments’ stated mission of rapid response.

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

Because license plates are in public view, law enforcement often treats their capture as low-sensitivity data, but civil-liberties advocates note that aggregated location histories become powerful tools for monitoring communities, and can be misused without strict oversight and retention limits. When private vendors, municipal budgets, and donor pressures intersect, the decision about what to retain and who can query it stops being merely technical — it becomes political.

Housing, Capital, and the Struggle for Space

The link between housing and policing is not new. Cities have long managed marginalized communities through both land-use policy and law enforcement. What makes the current moment different is the role of venture capital in simultaneously shaping both arenas.

If luxury real estate purchases drive up housing costs while drones and license-plate readers expand the reach of police surveillance, the result could be a city that feels increasingly hostile to the very residents most vulnerable to displacement. And without strong regulation, there is little to stop private investors from profiting on both sides of this equation.

As Dr. Buolomwini’s research shows, technological systems often reflect the biases of their creators and backers. The concern in Las Vegas is that Project Blue Sky and its allied surveillance systems may not just be about safety — they may be a blueprint for how surveillance and housing intersect under the banner of innovation.

Surveillance infrastructure rarely rolls back. Once the eyes in the sky and sensors on the street are in place, they become normalized — part of daily life. Project Blue Sky is more than a policing experiment. It’s a glimpse into a future where safety, surveillance, and housing markets overlap — a future Las Vegas must reckon with before the valley fills with eyes.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.