Las Vegas owes its very name to Latino history. In 1830, Mexican scout Rafael Rivera stumbled upon a fertile valley of meadows and springs while seeking water along the Old Spanish Trail. He called it Las Vegas — “the meadows.” Nearly two centuries later, the city built on that discovery still bears the imprint of Latino labor, culture, and enterprise.

Latino workers powered the casinos, laid the foundations of neighborhoods, and helped drive the city’s construction booms. Families built businesses that sustained not only themselves but entire communities. Yet, alongside stories of growth are chapters marked by exclusion and deportation — cycles of removal that continue to shape Latino life in Nevada and across the nation.

From Repatriation to the Bracero Program

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, Mexican and Mexican American families became scapegoats for widespread unemployment. Under so-called “Repatriation” campaigns, up to two million people of Mexican descent — more than half of them U.S. citizens — were deported or coerced into leaving the country. Entire families were uprooted, communities fractured, and businesses lost.

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

Less than a decade later, wartime labor shortages spurred the U.S. and Mexico to establish the Bracero Program in 1942, which recruited Mexican laborers to work in agriculture and railroads. While the program offered opportunities, it also entrenched a system of exploitation: low wages, poor conditions, and little protection for workers who sustained key industries.

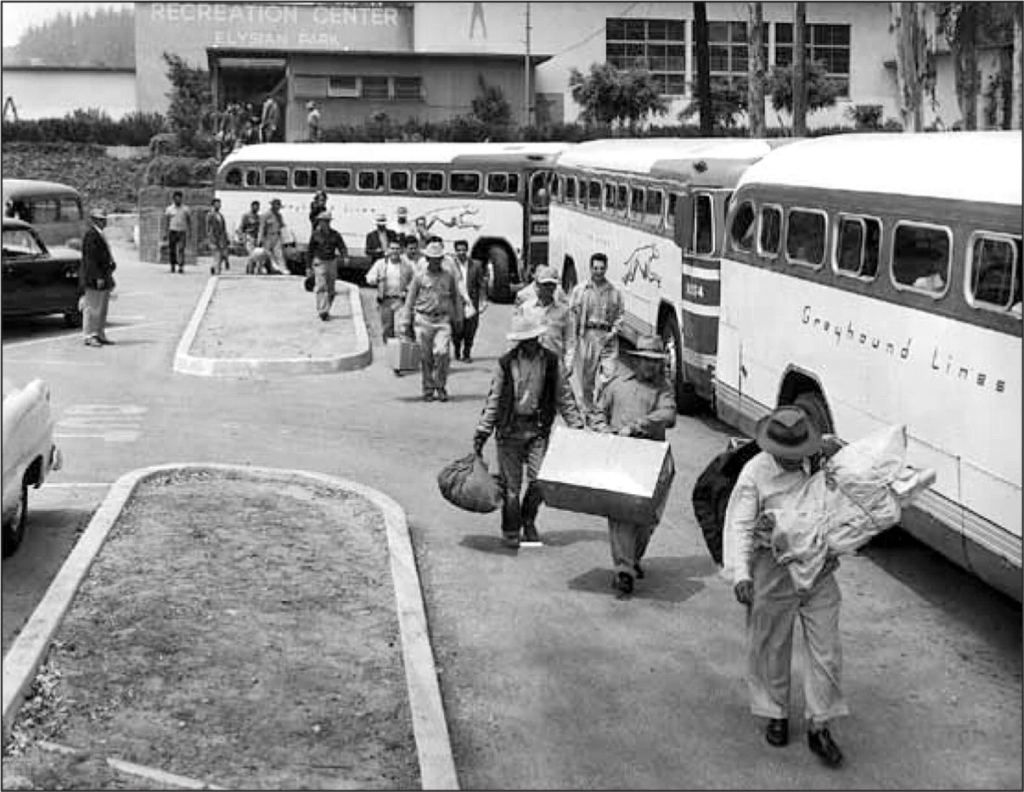

Operation Wetback and Its Scars

By 1954, amid renewed fears about “illegal immigration,” the U.S. launched Operation Wetback, one of the largest mass deportations in history. More than one million people of Mexican descent were rounded up — many of them U.S. citizens — and expelled. The operation left deep scars, particularly in border states and in cities like Las Vegas, where Mexican American families lived with the constant threat of raids and removals. The echoes of these programs remain. They created legacies of insecurity for Latino communities, where citizenship often offered no protection against suspicion or displacement.

Against this backdrop of resilience and struggle, the Latin Chamber of Commerce was founded in 1976. It began with just 50 businesses and grew into an organization representing more than 1,500 members. Its founders — local entrepreneurs, professionals, and community leaders — recognized the need for an institution that could amplify Latino voices in business and civic life.

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

The Chamber was more than a business association; it was a response to a history of exclusion. It sought to ensure that Latino economic power translated into political and social influence, protecting entrepreneurs and workers alike. For decades, it has served as a bridge between policy and community, advocating for inclusion in a city where Latino labor and business are central to growth.

That history is what makes the Chamber’s recent open endorsement of Governor Joe Lombardo so contentious. Lombardo has embraced policies linked to stricter immigration enforcement and mass deportation — policies that echo historical traumas like the 1930s Repatriation campaigns and Operation Wetback. Multiple attempts have been made to reach Peter Guzman, the Chamber’s president, for clarity. The questions remain unanswered:

- Process: Was this endorsement debated and approved by the Chamber’s Board of Directors, or made by Guzman alone?

- Community Impact: How does endorsing a politician aligned with deportation efforts benefit Latino small businesses, many of which rely on immigrant labor and undocumented entrepreneurs?

- Trust: How can undocumented entrepreneurs — who generated an estimated $317 million in business income in Nevada as recently as 2012 — see the Chamber as their advocate when its leadership endorses policies that threaten their livelihoods?

The Stakes for the Future

These unanswered questions could suggest two possible interpretations. One is that the Latin Chamber of Commerce itself has shifted away from its historic role as a defender of Latino business interests, toward alignment with political power. Another is that this is an issue of leadership accountability — that Guzman, without full process, spoke on behalf of thousands without their consent.

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

Either way, the implications are profound. Just as Rafael Rivera’s discovery helped shape Las Vegas nearly 200 years ago, today’s decisions by Latino institutions will shape the future of trust, representation, and opportunity for a community at the city’s core. The legacy of forced removal and economic struggle makes clear that endorsements are not just symbolic — they can determine whether Latino communities are empowered or once again made vulnerable in the city that bears their name.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.