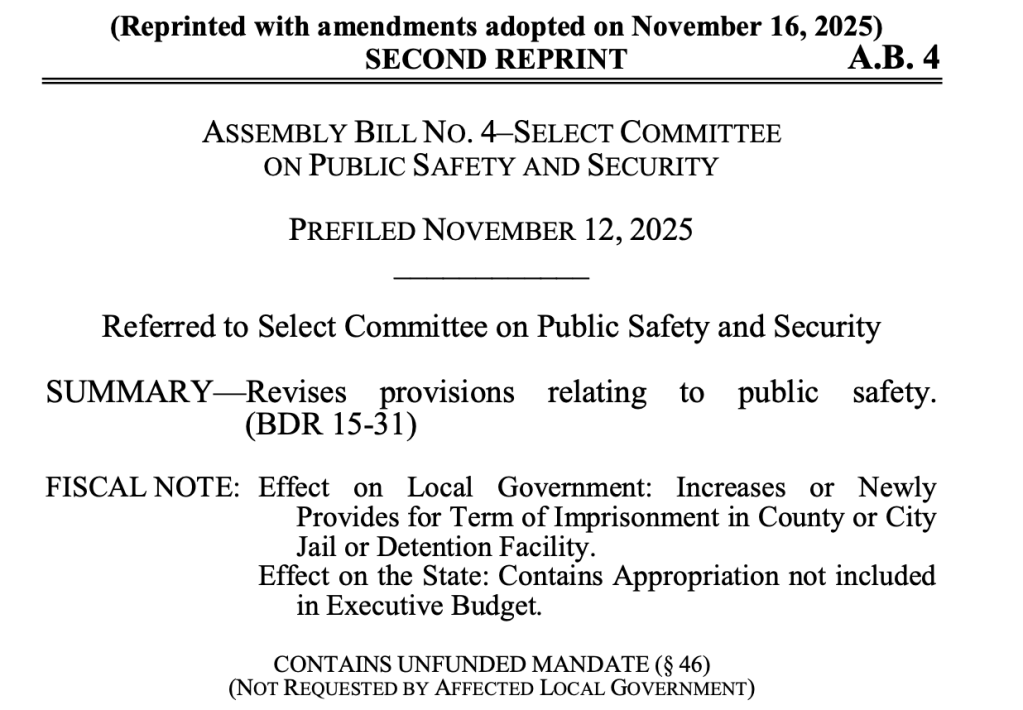

Assembly Bill No. 4 arrived in Nevada’s Legislature framed as a sweeping public-safety measure, one meant to respond to concerns about rising disorder in the state’s most heavily trafficked corridors.

It stretches sixty-eight pages and touches nearly every corner of the criminal code, creating new felonies, elevating penalties for old ones, and authorizing a series of judicial and correctional changes.

Supporters say it is a necessary realignment of public safety, giving local governments stronger tools in places where tourism, commerce, and dense foot traffic collide.

But the bill has also sparked a parallel conversation about who will bear the weight of those tools, and whether a law written as race-neutral can still deepen racial and economic divides.

The measure expands the definition of several crimes. A new offense is created for intentionally damaging property inside a retail establishment during a theft, and if the combined value reaches $750, it becomes a Category C felony.

Assault and battery provisions widen to protect hospitality workers and certain state or local employees whose duties put them in direct public contact.

The penalties for driving under the influence causing death increase, especially for individuals with prior convictions.

Acts that constitute stalking now include conduct creating fear for the immediate safety of a person in a dating relationship, and the legal definition of domestic violence expands to encompass kidnapping or attempts to solicit such offenses.

The bill also refines the prosecution of child sexual abuse material so that each depicted minor constitutes its own charge, including children represented in computer-generated images.

State officials who support these changes argue that the updates respond to observable shifts in criminal behavior, the pressures placed on workers in public-facing roles, and the need for consistency in the prosecution of certain offenses.

To them, the bill is an attempt to modernize the state’s response to crime without altering the fundamental character of Nevada law. They describe it as a tool to stabilize environments that millions of visitors depend on and that local economies require.

Yet the most debated part of the bill is a single structural mechanism nestled in the middle of the text.

AB 4 requires the Clark County Commission to designate certain geographic “corridors” where crime is said to pose a substantial risk to public safety and economic welfare.

These zones are expected to include the dense commercial centers of Las Vegas, where police presence is already the most concentrated.

Within these corridors, the law directs courts to impose a mandatory punishment on anyone who commits a second misdemeanor offense within two years: at least one year of exclusion from the corridor itself.

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

It is the creation of that boundary — the formal drawing of lines around public space — that has become the locus of concern.

Civil liberties advocates describe the penalty as a modern form of internal banishment, one that could disconnect a person from transportation hubs, employment centers, social services, and medical care.

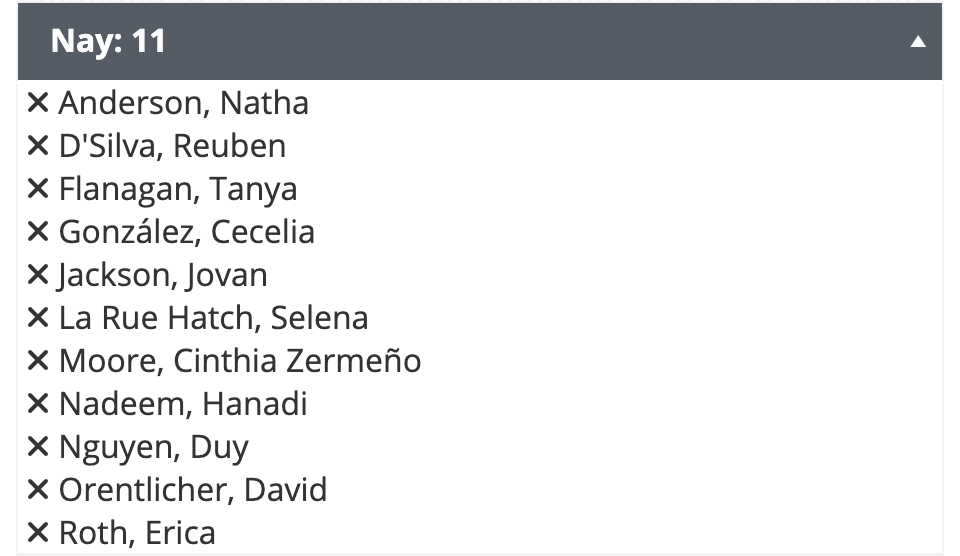

On paper, the rule applies equally to everyone. In practice, critics argue, exclusion zones function predictably within a system where arrests for low-level offenses fall disproportionately on Black, Indigenous, and Latino communities, and on people experiencing houselessness.

The bill does not mention race; its language is procedural, focused on offense categories and court authority.

But decades of data in Nevada and across the country show that misdemeanor enforcement is not race-neutral in effect.

Individuals from marginalized communities are more likely to be stopped, searched, cited, or arrested for low-level public-order violations such as trespassing, loitering, or jaywalking.

When laws broaden penalties for these types of offenses, the increased impact on those communities becomes a statistical certainty rather than a theoretical one.

Legal scholars describe this dynamic as disparate impact: the predictable outcome of policies passively shaped by longstanding inequities.

Supporters of the corridors see them differently. They argue that no community should have to navigate public spaces undermined by persistent disorder, and that businesses, workers, and visitors deserve predictable conditions.

They emphasize that the exclusion penalty only applies to repeat offenses within the same narrow geographic area, suggesting that it targets behavior patterns rather than populations.

For them, the ordinance is a matter of economic stewardship — a way to preserve the viability of a region that drives much of the state’s revenue.

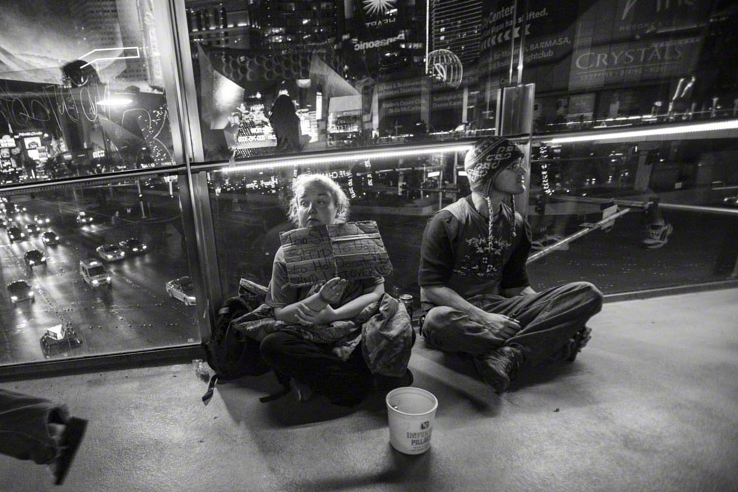

Opponents, meanwhile, call attention to the geography of enforcement. High-tourism corridors are also places where unhoused people sleep, seek shade, or access services because they are the few areas with consistent lighting, foot traffic, or proximity to transportation.

To critics, AB 4 reads not as a public-safety strategy but as a displacement strategy, one that shifts marginalized communities away from economic centers without providing any parallel investment in support, housing, or treatment.

They note that most misdemeanors linked to poverty — sleeping in public, obstructing walkways, minor property violations — are less about criminality than survival.

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

Underlying these arguments is a deeper question about the purpose of public space and who is seen as belonging in it.

Supporters speak of shared safety and shared economic interests. Critics speak of patterns that turn poverty into a crime and mobility into a privilege.

The debate includes not only legal concerns about overbreadth and due process but also the moral memory of how marginalized communities have historically experienced policing — not merely as regulation but as containment.

The bill also creates administrative and financial burdens for local government. Its corridors provision carries an unfunded mandate, requiring Clark County to establish the ordinance, create new court programs, and fulfill reporting requirements without additional state funding.

County officials have not yet detailed the full cost, but early estimates suggest significant staffing, training, and infrastructure needs.

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

3×3 Vinyl Sticker

Sliding scale $3.00-$8.00

AB 4 now stands at the intersection of two visions of safety. One asserts that maintaining order in concentrated public spaces protects both residents and the state’s economic lifeblood.

The other cautions that laws crafted under the banner of safety can reproduce old hierarchies if they rely on enforcement tools shaped by historic bias.

Nevada’s challenge — and the question at the heart of the bill — is whether public safety and public belonging can be legislated without erasing one in service of the other.

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.